In the current discussion about using a portion of the former Bruce-Monroe Elementary School site as a Build First site for the redevelopment of Park Morton, one of the arguments that’s been used by those not supporting this solution is that public land should not be given to a private developer. Yet, in an interesting historical twist, the reason for the large size of the former school site that exists today is that the Bruce-Monroe School required a Build First site for its construction, and the solution was to take the private property along Georgia Avenue between Columbia Road and Irving Street by eminent domain in order to create that school. From this perspective, with the school now gone, using the land along Georgia Avenue for a non-public purpose would be restoring it to its use prior to 1970.

This use of eminent domain for new schools was not a unique approach in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Unlike the last decade, during the 1960s DC schools were struggling with over enrollment. Rather than renovate and enlarge old school buildings which is the approach we use today, new schools were often built adjacent to existing schools, and upon completion, the old schools were razed. In Ward 1, this was not only the case with the old Monroe School and the Bruce-Monroe School that replaced it, but it was also the case with the old Morgan School in Adams Morgan which was replace by the Marie H. Reed Learning Center.

The old Monroe School on Columbia Road.

Discussions to replace the old Monroe School date to the mid-1960s. President Johnson was particularly interested in funding DC schools, though would often see his proposed budget cut by Congress or the District Commissioners. In 1966, it was reported that the funding for a new building to replace the Monroe and Bruce schools had been cut from the budget.

This detail from the 1968 Baist’s Real Estate Atlas shows that the Georgia Avenue frontage of the Bruce Monroe site was originally private property with commercial buildings.

1969 was a crucial year for the new Bruce-Monroe school. It was listed as one of 15 new schools that the school system was seeking funding for at the beginning of the year, yet the District School Board decided in February to chop $8 million from its $55 million request resulting in plans for Bruce-Monroe to be shelved. This decision was quickly reversed on April 1st as the $8 million was restored to the original budget request … and the request was approved by the District City Council on April 3rd. However, the total District budget request for 1970 was $728.2 million and President Johnson had already announced a budget of $702 million for the District in January. Perhaps in partial response to this, the school board once again reversed itself on April 25th and removed funding for the new Bruce-Monroe School.

Despite the back and forth funding drama unfolding in April 1969, the project appears to have gotten a delayed approval after a meeting with the community to discuss the proposed replacement of the Monroe School held at the end of May. Over a year later, in September 1970, notices began to appear in the Washington Evening Star announcing the government’s intent to take the private property abutting the school on Georgia Avenue to use for municipal purposes — that being, a new school. The Department of General Services began taking sealed bids on April 23, 1971 with a closing date of May 24th.

Ground was broken on the new school on October 5, 1971, and the $4 million school was completed and ready to serve the community in the fall of 1973. Upon its completion, the old Monroe School was razed save for the old auditorium which was connected to the new school by a causeway.

(Lisa Nix (left) and Jonathan Brooks (right) break ground for the new Bruce Monroe, October 5, 1971).

(Lisa Nix (left) and Jonathan Brooks (right) break ground for the new Bruce Monroe, October 5, 1971).

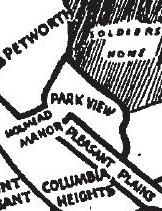

"The territory comprising Park View extends from Gresham Street north to Rock Creek Church Road, and from Georgia Avenue to the Soldiers' Home grounds, including the triangle bounded by Park Road, Georgia Avenue, and New Hampshire Avenue" (from Directory and History of Park View, 1921.)

"The territory comprising Park View extends from Gresham Street north to Rock Creek Church Road, and from Georgia Avenue to the Soldiers' Home grounds, including the triangle bounded by Park Road, Georgia Avenue, and New Hampshire Avenue" (from Directory and History of Park View, 1921.)